Cacuqecig

Postman

- Joined

- Oct 11, 2016

- Messages

- 212

Part 2: An analysis of the correlation between Electronic Cigarette prevalence and smoking cessation rate

We concluded at the end of Part 1 that Electronic Cigarette use among all groups (with the exception of a moderate increase in long-term ex-smokers) in England has remained stable since 2013. There is no ground, therefore, to argue that smoking cessation since 2013 is caused by the increasing prevalence of Electronic Cigarettes because the assumed increase is merely imaginary as we have seen from the graphs. Our question here is, what has caused the consistent decline in cigarette smoking prevalence since 2013?

To attribute the cause of smoking cessation to Electronic Cigarette use is to fail to observe the steady decline in cigarette smoking prevalence prior to the boom of Electronic Cigarette market in 2011. The same factor which caused the decline may have continued regardless the rise of Electronic Cigarette. It also fails to recognize the prevalence of NRT among smokers and the possible effect thereof. However, because of insufficient data, or rather the difficulty of fully understanding so tangled and complicated a matter, there is, till now, no conclusion as to what has caused the consistent decline in cigarette smoking prevalence since 2013. We can only wish to, with the aid of available statistics, reach a possible though not proved assumption that agrees with what the data tells us.

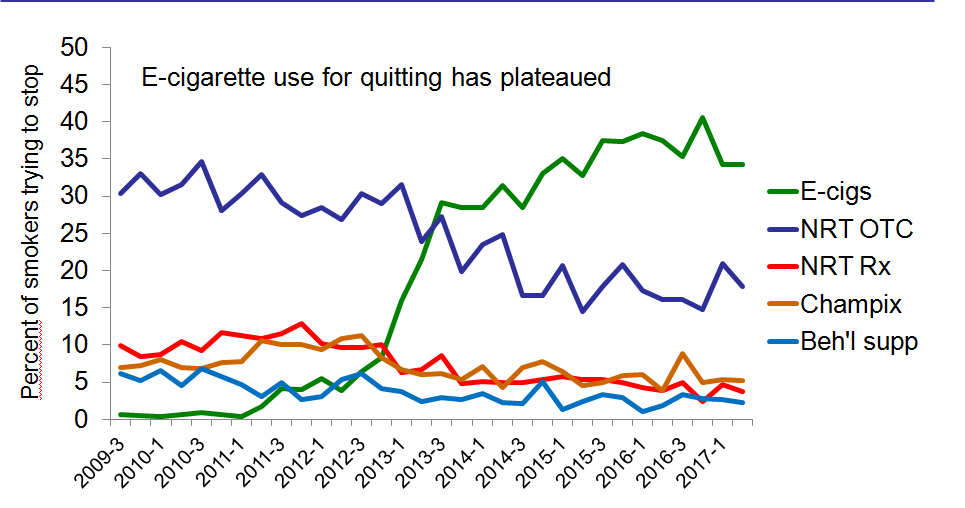

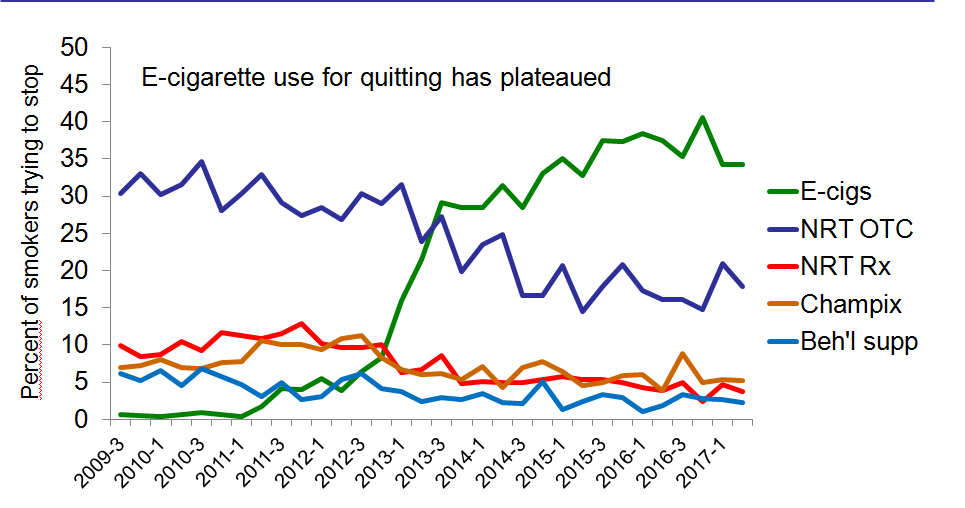

Take a look at the graph below.

N=12859 adults who smoke and tried to stop or who stopped in the past year; method is

coded as any (not exclusive) use

As we can see from the graph, E-cigarette use for quitting has plateaued since 2013. Also, something not to be overlooked is that, prior to 2011, the year when Electronic Cigarette started its ascension, the prevalence of NRT OTC was at almost as high as that of E-cig in present day. Although popularity of NRT OTC has since plummeted with the rise of Electronic Cigarettes, it is still a force to be reckoned with, 20% of adults who smoke and tried to stop or who stopped in the past year still using NRT OTC as their aid---a figure not to be slighted. It is also not clear whether the declining prevalence of NRT OTC is caused by the increasing prevalence of Electronic Cigarettes, as we only see from the graph a conjunction of these two trends, but not causality. But this graph does tell us that, since 2011, there has been a large proportion of smokers who try to stop smoking that employ Electronic Cigarettes as their means of quitting.

So far, based on the data which we have presented, we cannot conclude that the steady decline of cigarette prevalence is caused by the use of Electronic Cigarettes because 1. we are not sure whether the factor which caused the decline prior to 2011 is not at work even now; 2. we are not sure how important a role NRT OTC played in the decline. Further researches might present the exact effectiveness of NRT OTC in smoke cessation but as far as this article is concerned, this is a factor that cannot be disregarded.

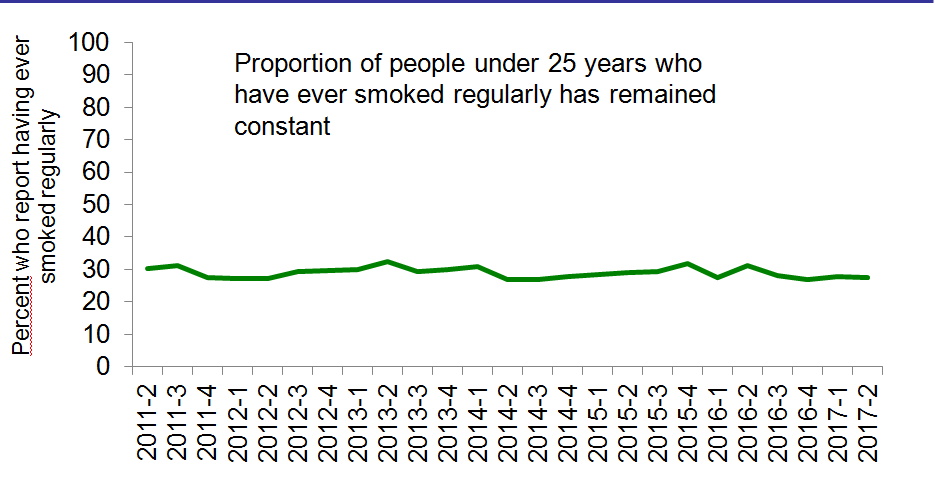

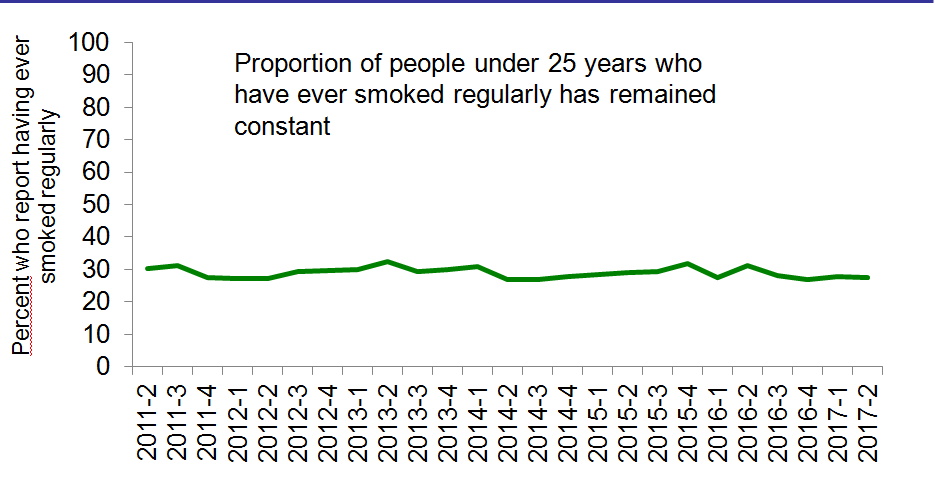

Take a look at the graph below which shows that the proportion of people under 25 years who have ever smoked regularly has remained constant.

Take-up of smoking

N=19722 people aged 16-24

This shows that, Electronic Cigarettes and other agents of smoking cessation do not prevent young people from taking up smoking, as some might claim. Instead, their effect, if there be any, is that they provide a substitute for cigarette smokers.

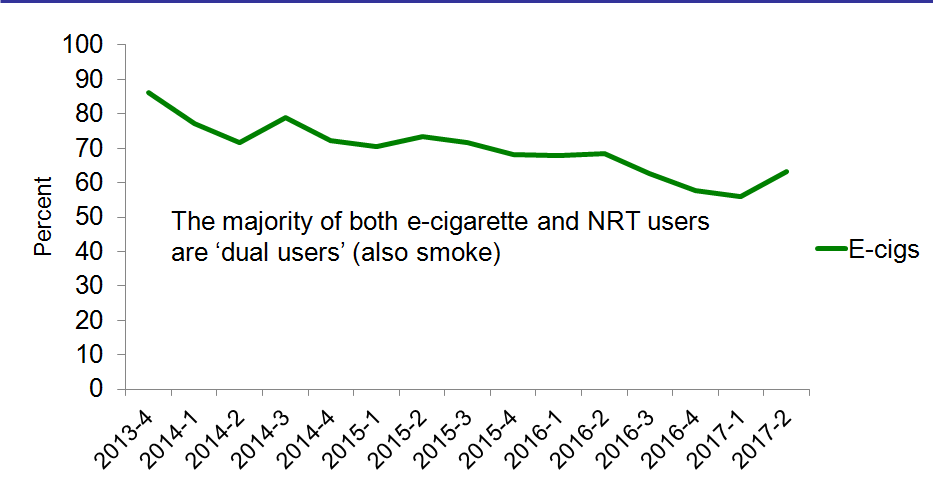

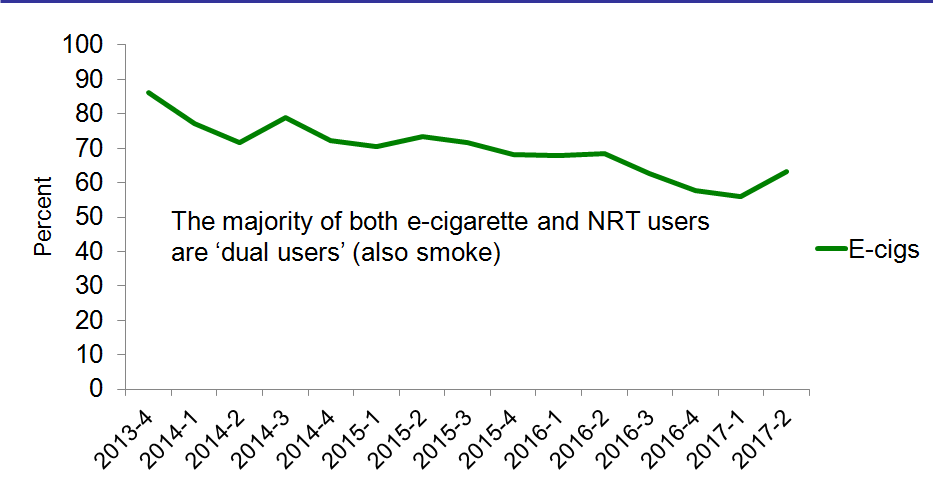

Take a look at two more graphs below.

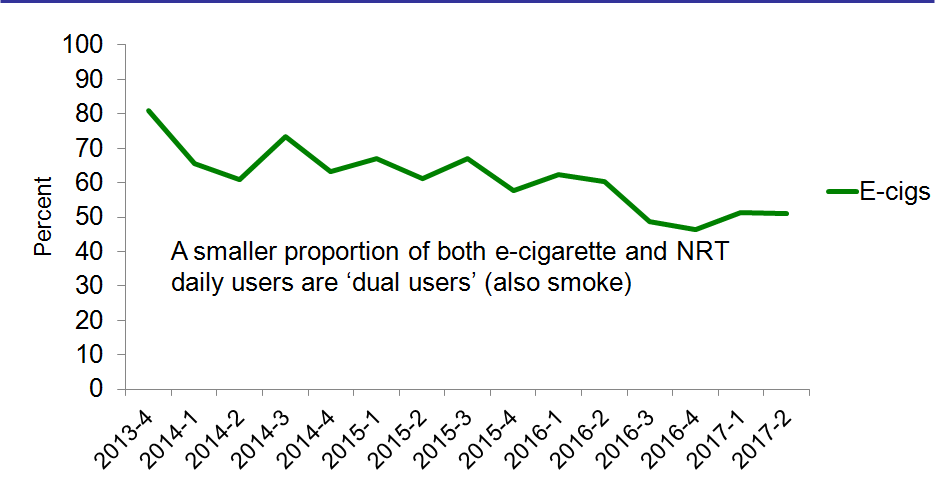

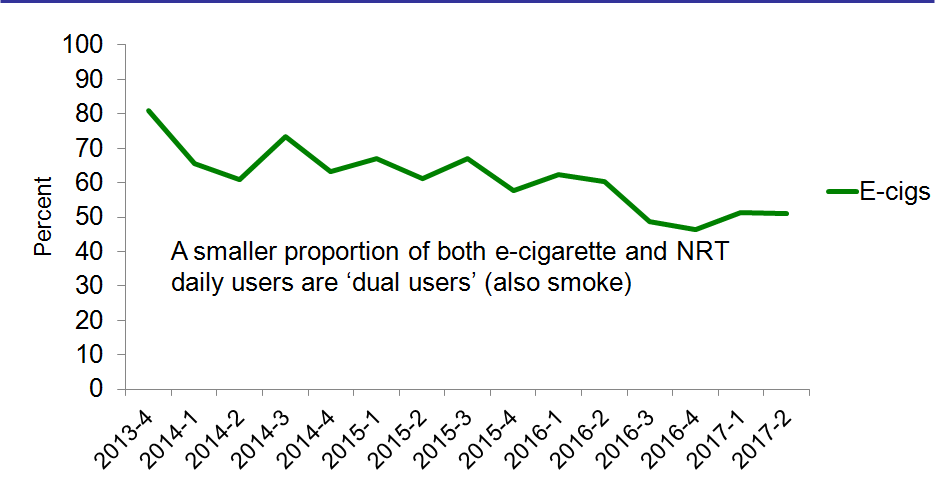

Proportion of e-cigarettes users who are smokers

N=3869 e-cigarette users users of adults

Proportion of daily e-cigarette users who are smokers

N=2193 e-cigarette users and of adults

As it is clear from the graphs, the majority of Electronic Cigarette users are dual users (also smoke), and even among daily Electronic Cigarette users, a majority, though to a lesser extent, are dual users. This shows that the employment of Electronic Cigarettes does not deter cigarette smoking as effectively as propaganda presented it to be.

It is also clear that from 2013 to 2017, the amount of dual users reduced moderately in proportion. Considering the fact that the number of Electronic Cigarette users remained stable since 2013, we may infer that the number of dual users reduced roughly by one-third as seen in both the graphs above. Not considering other factors that may have played a role in this reduction, it may, judging from the above graphs alone, seem reasonable to conclude that Electronic Cigarettes do help smokers quit. But again, the reduction maybe due to the exit of Electronic Cigarette using by dual users while the new entries are people who already quitted smoking. Therefore it is not clear from these two graphs whether Electronic Cigarettes can really help smokers quit.

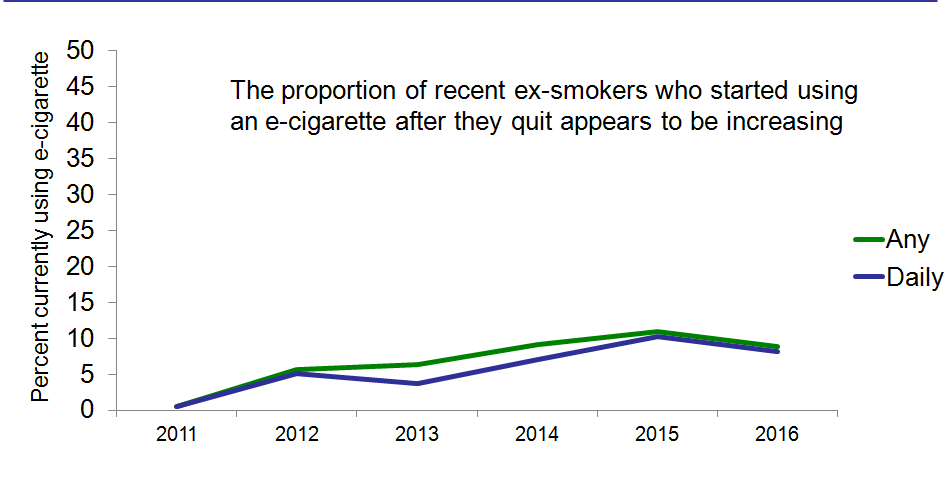

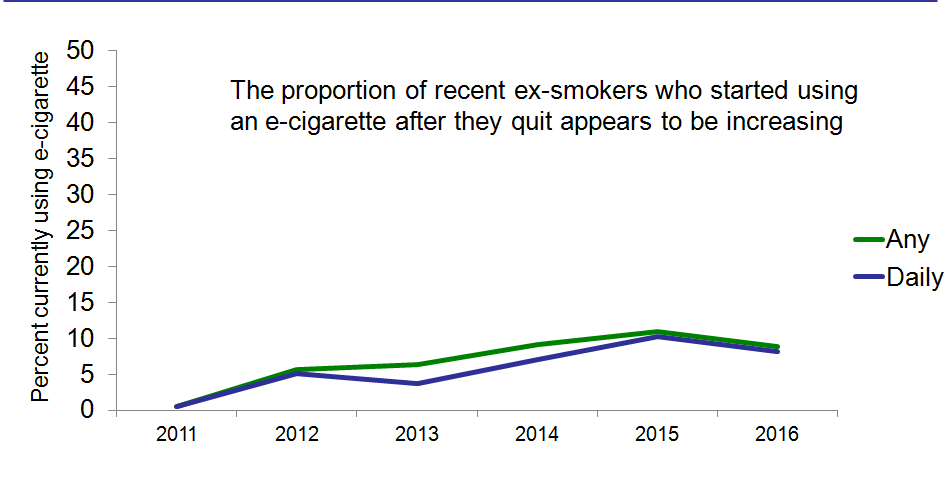

Take a look at another interesting graph.

Current e-cigarette use after quitting

N=941 adults who stopped in the past year and did not report using an e-cigarette to help during the quit attem

This shows that the proportion of recent ex-smokers who started using an e-cigarette after they quit appears to be increasing. Note that these adults are those who in the past year succeeded in quitting smoking and did not report using an E-cigarette to help during the quit attempt. We have to observe that only less than ten percent of the adults who quitted smoking in the past year are currently E-cigarette users, which casts a serious shadow upon the argument that that they employed Electronic Cigarette as a means to fortify their achievement.

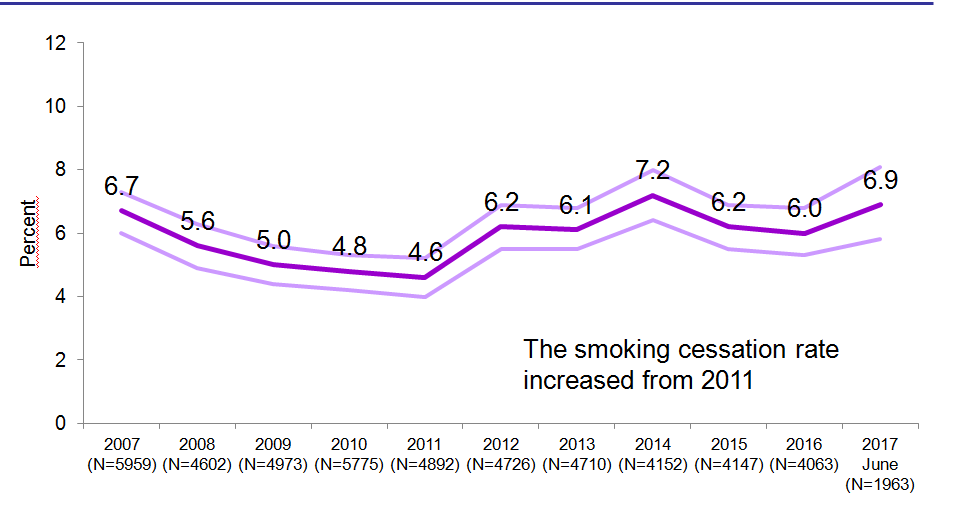

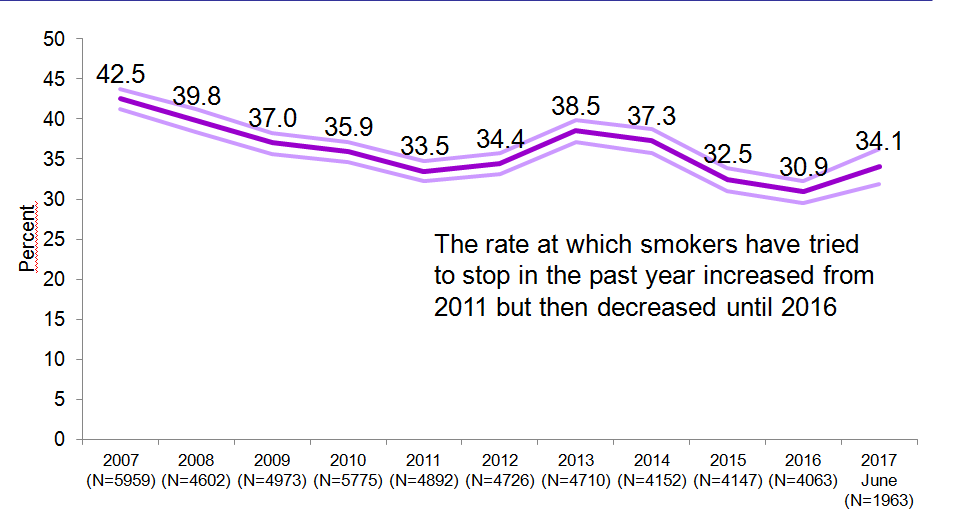

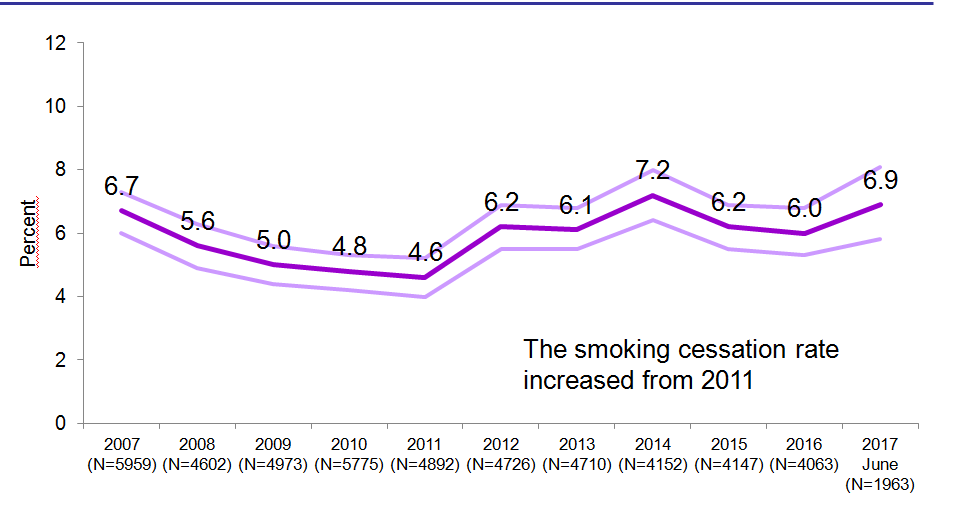

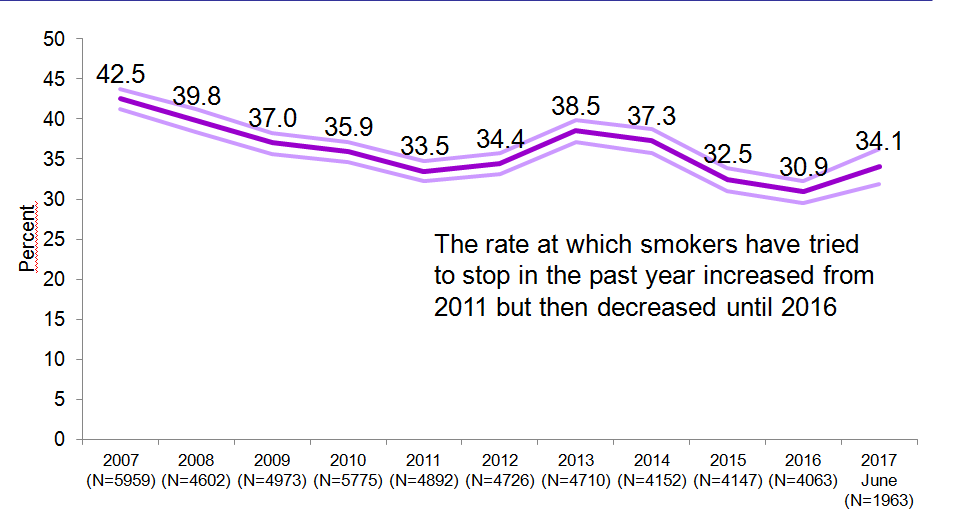

To further test the effectiveness of Electronic Cigarettes as an agent of smoking cessation, let's take a look at two more graphs below.

Stopped smoking in past 12 months

Base: Adults who smoked in the past year

Tried to stop smoking in past year

Base: Adults who smoked in the past year

As we can read from the first graph, the smoking cessation rate increased since 2011. This coincided with the increase of the prevalence of use of electronic Cigarettes, but the trajectories for smoking cessation and quit success differ from that of prevalence of use of e-cigarettes. The proportion of smokers who have tried to stop in the past year increased from 2011 but then decreased until 2016. This different trajectory also does not support the argument that the use of Electronic Cigarettes helped smokers quit.

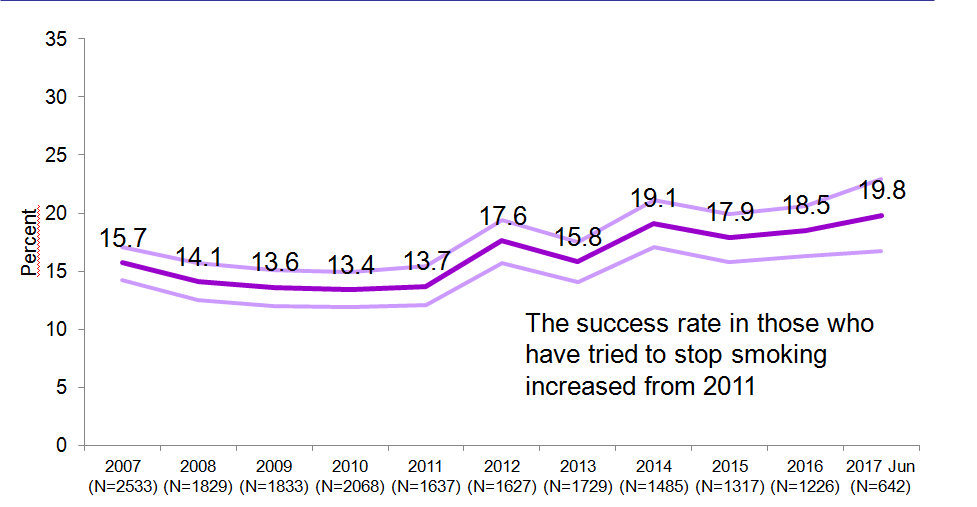

One last graph to look at

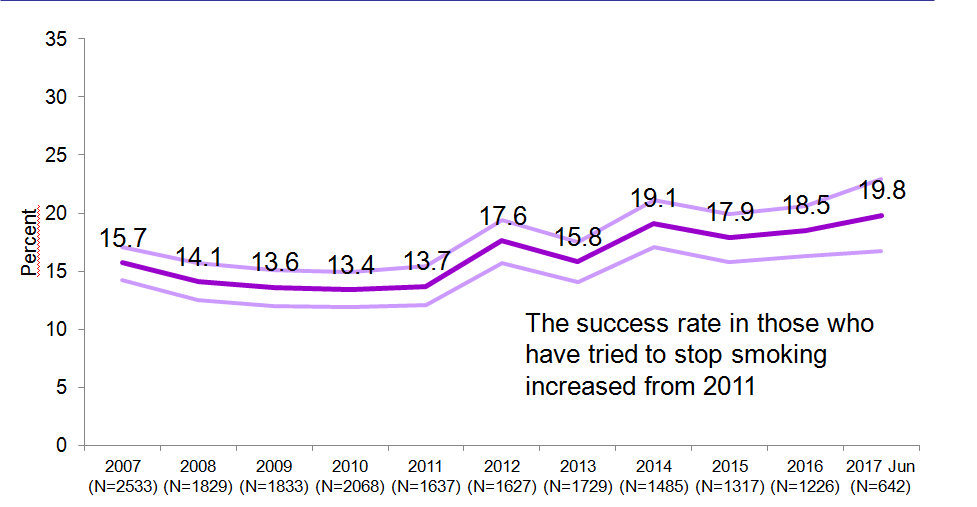

Success rate for stopping in those who tried

Base: Smokers who tried to stop in the past year

The graph shows that the success rate in those who have tried to stop smoking increased from 2011. But again, the trajectory do not agree with that of the prevalence of the use of Electronic Cigarettes. Therefore the best that could be concluded is that there is a conjunction of these two events, as we have seen from the analysis of all the other graphs in this article, but not causality.

In conclusion, though it being contrary to public conception, we have to assert, after the presentation of Electronic Cigarette use among different groups in England and in Part 1 and the analysis of the correlation between Electronic Cigarette prevalence and smoking cessation rate in part 2, that there is no clear causal relation between the use of Electronic Cigarette use and smoking cessation. Therefore the argument that Electronic Cigarettes help smokers quit, as far as this article and the statistics it referred to, is ungrounded.

We concluded at the end of Part 1 that Electronic Cigarette use among all groups (with the exception of a moderate increase in long-term ex-smokers) in England has remained stable since 2013. There is no ground, therefore, to argue that smoking cessation since 2013 is caused by the increasing prevalence of Electronic Cigarettes because the assumed increase is merely imaginary as we have seen from the graphs. Our question here is, what has caused the consistent decline in cigarette smoking prevalence since 2013?

To attribute the cause of smoking cessation to Electronic Cigarette use is to fail to observe the steady decline in cigarette smoking prevalence prior to the boom of Electronic Cigarette market in 2011. The same factor which caused the decline may have continued regardless the rise of Electronic Cigarette. It also fails to recognize the prevalence of NRT among smokers and the possible effect thereof. However, because of insufficient data, or rather the difficulty of fully understanding so tangled and complicated a matter, there is, till now, no conclusion as to what has caused the consistent decline in cigarette smoking prevalence since 2013. We can only wish to, with the aid of available statistics, reach a possible though not proved assumption that agrees with what the data tells us.

Take a look at the graph below.

N=12859 adults who smoke and tried to stop or who stopped in the past year; method is

coded as any (not exclusive) use

As we can see from the graph, E-cigarette use for quitting has plateaued since 2013. Also, something not to be overlooked is that, prior to 2011, the year when Electronic Cigarette started its ascension, the prevalence of NRT OTC was at almost as high as that of E-cig in present day. Although popularity of NRT OTC has since plummeted with the rise of Electronic Cigarettes, it is still a force to be reckoned with, 20% of adults who smoke and tried to stop or who stopped in the past year still using NRT OTC as their aid---a figure not to be slighted. It is also not clear whether the declining prevalence of NRT OTC is caused by the increasing prevalence of Electronic Cigarettes, as we only see from the graph a conjunction of these two trends, but not causality. But this graph does tell us that, since 2011, there has been a large proportion of smokers who try to stop smoking that employ Electronic Cigarettes as their means of quitting.

So far, based on the data which we have presented, we cannot conclude that the steady decline of cigarette prevalence is caused by the use of Electronic Cigarettes because 1. we are not sure whether the factor which caused the decline prior to 2011 is not at work even now; 2. we are not sure how important a role NRT OTC played in the decline. Further researches might present the exact effectiveness of NRT OTC in smoke cessation but as far as this article is concerned, this is a factor that cannot be disregarded.

Take a look at the graph below which shows that the proportion of people under 25 years who have ever smoked regularly has remained constant.

Take-up of smoking

N=19722 people aged 16-24

This shows that, Electronic Cigarettes and other agents of smoking cessation do not prevent young people from taking up smoking, as some might claim. Instead, their effect, if there be any, is that they provide a substitute for cigarette smokers.

Take a look at two more graphs below.

Proportion of e-cigarettes users who are smokers

N=3869 e-cigarette users users of adults

Proportion of daily e-cigarette users who are smokers

N=2193 e-cigarette users and of adults

As it is clear from the graphs, the majority of Electronic Cigarette users are dual users (also smoke), and even among daily Electronic Cigarette users, a majority, though to a lesser extent, are dual users. This shows that the employment of Electronic Cigarettes does not deter cigarette smoking as effectively as propaganda presented it to be.

It is also clear that from 2013 to 2017, the amount of dual users reduced moderately in proportion. Considering the fact that the number of Electronic Cigarette users remained stable since 2013, we may infer that the number of dual users reduced roughly by one-third as seen in both the graphs above. Not considering other factors that may have played a role in this reduction, it may, judging from the above graphs alone, seem reasonable to conclude that Electronic Cigarettes do help smokers quit. But again, the reduction maybe due to the exit of Electronic Cigarette using by dual users while the new entries are people who already quitted smoking. Therefore it is not clear from these two graphs whether Electronic Cigarettes can really help smokers quit.

Take a look at another interesting graph.

Current e-cigarette use after quitting

N=941 adults who stopped in the past year and did not report using an e-cigarette to help during the quit attem

This shows that the proportion of recent ex-smokers who started using an e-cigarette after they quit appears to be increasing. Note that these adults are those who in the past year succeeded in quitting smoking and did not report using an E-cigarette to help during the quit attempt. We have to observe that only less than ten percent of the adults who quitted smoking in the past year are currently E-cigarette users, which casts a serious shadow upon the argument that that they employed Electronic Cigarette as a means to fortify their achievement.

To further test the effectiveness of Electronic Cigarettes as an agent of smoking cessation, let's take a look at two more graphs below.

Stopped smoking in past 12 months

Base: Adults who smoked in the past year

Tried to stop smoking in past year

Base: Adults who smoked in the past year

As we can read from the first graph, the smoking cessation rate increased since 2011. This coincided with the increase of the prevalence of use of electronic Cigarettes, but the trajectories for smoking cessation and quit success differ from that of prevalence of use of e-cigarettes. The proportion of smokers who have tried to stop in the past year increased from 2011 but then decreased until 2016. This different trajectory also does not support the argument that the use of Electronic Cigarettes helped smokers quit.

One last graph to look at

Success rate for stopping in those who tried

Base: Smokers who tried to stop in the past year

The graph shows that the success rate in those who have tried to stop smoking increased from 2011. But again, the trajectory do not agree with that of the prevalence of the use of Electronic Cigarettes. Therefore the best that could be concluded is that there is a conjunction of these two events, as we have seen from the analysis of all the other graphs in this article, but not causality.

In conclusion, though it being contrary to public conception, we have to assert, after the presentation of Electronic Cigarette use among different groups in England and in Part 1 and the analysis of the correlation between Electronic Cigarette prevalence and smoking cessation rate in part 2, that there is no clear causal relation between the use of Electronic Cigarette use and smoking cessation. Therefore the argument that Electronic Cigarettes help smokers quit, as far as this article and the statistics it referred to, is ungrounded.